Emma’s type 2 diabetes diagnosis flipped her life upside down. “It is like carrying a baby that never grows,” she states. “It is irritating you as soon as you wake up.” Every bit of food must be carefully selected in case it spikes her blood sugar levels, which could drive her to pass out or worse.

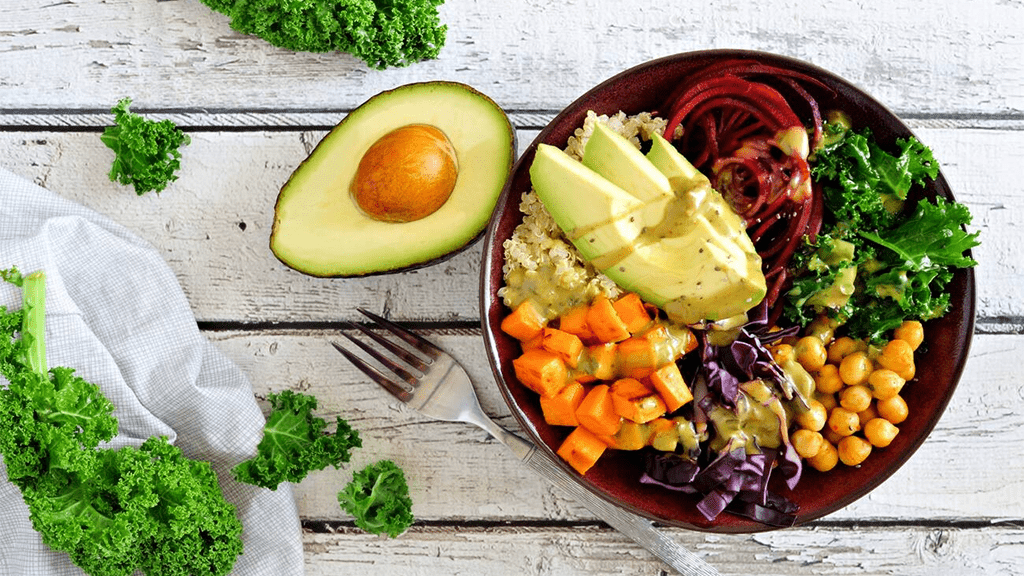

The perfect diet for someone with Emma’s condition would include:

That diet has been shown to slow down or even flip the progression of type 2 diabetes and help stop it from happening in the first place. But that has been a diet she has floundered to access.

What if such a diet could be prescribed in the same way as medicine, as an authoritarian intervention, funded by the government, readily available, and with abundance of support and information to help prevent or treat illness? The concept of “food as medicine” is gaining movement worldwide as scientists and doctors look for ways to use food in a targeted manner to improve health.

Healthy food is not just crucial for diabetes, states Prof Jason Wu, a University of New South Wales nutrition epidemiologist and head of the nutrition science program at the George Institute for Global Health in Sydney. He expresses many of the “top killers” in western societies, from diabetes to cardiovascular condition and some cancers, are linked to lifestyle, “and diet is one of the major reasons.”

Years of campaigns on healthy eating have failed to make much of a dent in Australia’s worsening swiftness of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Wu and many others say the issue is systemic barriers – such as cost, accessibility, accessibility, and education – that no amount of public health messaging advocating for healthy diets can overpower.

Advocates assume better targeted, supported, and funded prescriptive methods are needed, and that’s where the idea of food as medicine comes in. Wu and colleagues lately conducted a study involving 50 people with type 2 diabetes who were discovering it hard to afford enough food. The group was “prescribed” a free box of fresh vegetables, fruit, whole grains, lean meats, and dairy – given to their home every week. They also had regular access to a dietician and were provided recipes and advice on preparing healthy food using the ingredients.

Emma was one of the study participants. “I would open up these boxes and it was things that I hadn’t eaten in a long time or things that I just didn’t think were an option,” she says. Instead of a burger for breakfast, she ate the fruit; instead of chips, she had nuts and seeds.

The study lasted only three months, but in that time, the “produce prescriptions” significantly improved diet quality and food security for those involved. And there were other unexpected benefits: overall, the participants improved their cholesterol levels, lost weight, and ate less unhealthy food.

The affordability problem

Wu wants to witness food as medicine becomes an intrinsic part of healthcare in deterring and treating disease. It is not to suggest one can consume themselves out of terminal illness, but food can have a powerful effect on health and some disease.

“The reason why we use food as therapy is that healthcare needs to shift,” he says. “Inside healthcare itself, healthy food and honestly just healthy physical activity does not get anywhere near adequate attention it should get.”

He’s driving for food prescriptions to become subsidized and accessible like pharmaceutical prescriptions. “We spend billions of dollars every year paying for medications or surgeries that are essentially downstream consequences of unhealthy diets,” Wu says. He says some healthcare dollars should be diverted to pay for or subsidize evidence-based healthy foods for patients with these lifestyle-related diseases, particularly those already experiencing food insecurity.

As well as prevention – such as switching from processed carbohydrates to wholegrains to avoid pre-diabetes developing into a full-blown disease – some studies suggest food prescriptions be used for people already affected by a disease. For example, a recent study from the University of Newcastle found a daily handful of almonds helped relieve constipation in people with kidney disease undergoing the blood-filtering process of haemodialysis.

Clare Collins, a nutrition and dietetics professor at the University of Newcastle, states she would like to see nutrition managed care plans – equivalent to the mental health treatment plans currently subsidized by Medicare – that provide people access to dieticians and nutritionists who can assist in overcoming at least some of the obstacles to healthy eating.

At the juncture, a Medicare-subsidised chronic disease management plan – for managing diseases such as type 2 diabetes – includes the choice of a single appointment with a dietitian as one of many allied health professionals open for a limited number of subsidized appointments.

“If you really want to assist someone, totally change the trajectory,” she states. “It’s not going to be getting one of five visits and a medicine; it needs that whole support structure.” While Collins isn’t opposed to the idea of food prescriptions, she says it doesn’t go far enough in handling the systemic barriers that make it problematic for people to eat a healthy diet.